ALL HAIL THE GIANT SHINY DISC!

A personal history of home theater and the laserdisc format.

By Sam Hatch

As a dyed-in-the-wool film fanatic growing up during the 70s and 80s, it was an interesting span of time in which to experience the newly charted waters of 'watching films at home'. The specter of Home Theater loomed large in my mind (as evidenced by early school drawings involving gigantic TV screens that displayed theoretical home videos of Star Wars). In a short number of years such things were possible, but VHS and cable weren't the formats that eventually led to my obsession with home theater – it was a now nearly forgotten format called Laserdisc.

For those unfamiliar with these outrageously cool 12-inch platters, check out some of the Laserdisc info sites on our links page. What began as a late-70's video failure eventually found its foothold as a niche format catering to the needs of hardcore film fanatics. This was mainly because it was the primary source for films presented in their original theatrical aspect ratio.

For those unfamiliar with these outrageously cool 12-inch platters, check out some of the Laserdisc info sites on our links page. What began as a late-70's video failure eventually found its foothold as a niche format catering to the needs of hardcore film fanatics. This was mainly because it was the primary source for films presented in their original theatrical aspect ratio.

I first met the videodisc format in the very early Eighties when I was spending quite a bit of time in the Avon Video Studio rental store. Nestled in one corner was a brand-spanking new MCA Disc-O-Vision player, and in it was the only laserdisc on the premises – Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band. Not nearly as cool as Star Wars, but an introduction nonetheless. Shortly thereafter, MCA's monicker died and the format went into hibernation, but the appeal of those shiny silver discs lingered on.

My first encounter with any form of home theater (greater than watching televised films on a mono TV set) occurred in 1981. NBC was showing a promo/fluff tie-in with the Ray Harryhausen spectacle Clash of the Titans, which was one of my favorites at the time. My mother clued me into the fact that sometimes you could pick up the audio from television stations at the very low end of the FM dial.

Sure enough, we were able to enhance the Titans advertisement with dual-mono sound emanating from our teeny Technics receiver. A few years later when the family bought our first VCR (a big, boxy 80's looking Emerson thingy), the thought again arose of hooking it up to the stereo. This was fueled by the cable broadcast of a cinematic gem entitled Repo Man. The ability to blare the opening Iggy Pop number in blissfully hissy mono sound was a joyful experience. The notion of tying the soundstage to the physical position of the monitor had not yet crossed my mind, so much of these early experiences involved all sound emanating from the left of the viewing position.

And this was the paradigm for quite a while. Mono (and eventually stereo in the late 80s) audio fed through a receiver and speakers that were located at a completely wrong position in the listening room. In the mid-Eighties plenty of these experiences involved watching a syndicated cartoon called Robotech. As a nerdy comics fan, I had been informed of the stylish realm of Japanese manga comics and by relation of anime TV shows. I had seen Battle of the Planets in the 70s, but lived too far away from New York to have encountered the true groundbreaker that was Star Blazers. In time Voltron hit American airwaves, but the storylines were too episodic for my liking - too much like Battle of the Planets. What I was waiting for was one of the brilliant space operas I had read about in magazines.

And then Robotech hit. A bit of an anomaly, it was the product of an American producer taking three separate Japanese anime entities and shoehorning them together into one beefy new narrative. The segment that was affected the least by this meddling was also my favorite, the Macross saga. My love of this story led me to seek out bootlegged videos of other Japanese anime such as Space Captain Harlock and the Dirty Pair series. These bootlegs were often found at sci-fi and comic conventions, and as hard as it is to believe in today's Adult Swim/Toonami world, were only available in Japanese with no subtitles. A ton of us hardcore freaks were watching tape after tape of stories that we could only understand on a visual (and emotional) level. And it was cool.

Eventually I came to realize that all of these tapes were being dubbed off of imported Japanese laserdiscs, as that format was immensely popular across the Pacific. This pushed me into ordering catalogs from several West Coast dealers selling anime laserdiscs at what seemed enormous sums of money. Still, it was with this in mind that I decided that a laserdisc player was something to be acquired as soon as possible. And so it was that I landed my first real job, complete with a steady income and the promise of a tax refund.

In the meantime, a friend of the family had secretly picked up a Pioneer LD player in the early nineties, when the format was finding new legs in America. I had heard about the possibilities of extras and director's commentary tracks, and had recently seen a copy of the Aliens director's cut boxed set in a Coconuts store. Needless to say, it was a very jealous Sam who went over to actually view the disc for the first time at this guy's house. Upon arriving, I found that he had set up the basement as a viewing environment - with a reclining couch facing the TV, loudspeakers set at equidistant lengths from the monitor, and two additional speakers set behind the seating area. All of which were being fed by a Pioneer ProLogic surround receiver.

I know this all sounds terribly mundane now, but at the time it was almost as important as a first kiss, as revelatory as first learning that the earth wasn't flat (Sorry, Flat Earth Society). And so I sat down and first experienced James Cameron's long cut of Aliens, a disc that is now generally considered a poor transfer. At the time, I was mesmerized by the amount of detail visible, as Laserdisc was capable of delivering so much more than the VHS format. And by this point the need of a player for merely watching imported anime seemed a tad narrow-minded. I needed one of these things to watch everything! In surround sound! In widescreen! In sharp focus!

Tax time came quickly, and with cash in hand I ran to the Enfield Square Mall to scope out possibilities. The Service Merchandise store nearby turned up nothing for players, so I opted to honor my tried and true tradition of purchasing some kind of software before buying the hardware on which to play it. The ploy had worked with CDs, so I figured owning a laserdisc or two would force my hand into buying a player come hell or high water. Oddly, the first disc I picked up (Alien3) was also the first one I owned that suffered from laser rot, which I will discuss later.

I had never seen much in the way of electronics in Filene's before, but my mother urged me to check it out before giving up for the night (Thanks, Mom!).  Sure enough, a steely grey Sony MDP-333 display model sat on a markdown shelf upstairs, sad from a year of neglect and marked down to a reasonable $350 dollars or so. At the time there was no Home Theater Forum to aid in purchasing decisions, so I had no way of knowing that Sony laserdisc players were looked down upon as a mechanical form of Satan. Regardless, I dragged more than my money's worth out of the deck, which still sits on a shelf not ten feet in front of me as I type.

Sure enough, a steely grey Sony MDP-333 display model sat on a markdown shelf upstairs, sad from a year of neglect and marked down to a reasonable $350 dollars or so. At the time there was no Home Theater Forum to aid in purchasing decisions, so I had no way of knowing that Sony laserdisc players were looked down upon as a mechanical form of Satan. Regardless, I dragged more than my money's worth out of the deck, which still sits on a shelf not ten feet in front of me as I type.

It was loaded with cool features. An S-Video output? What the hell was that? A toslink digital out port? I was dying to play with it, but I had nothing to connect it to. (In fact, it was a delight to finally hook it up for the first time nearly ten years later. Almost like having sex for the first time, but less messy and with more ones and zeros.)

And although the player had no dual-side ability or digital video effects, there were plenty of bells and whistles to keep me entertained as I hooked it up to the family TV and stereo receiver. I even managed to reenergize my love for CDs, as I learned that some discs contained index tracks that only my LD player could access. Now I could jump from part one of Rush's 2112 (Overture) to part four (Presentation) with a few button pushes. Wahoo!

And yes, when I mentioned dual side ability, I was referencing the fact that laserdiscs could only fit (at the most) one hour of programming content per side. So for most regular length films, one had to flip sides once and usually swap discs once as well. This bothered plenty of folks to no end, but as a film fanatic I always thought it felt like I was changing reels in a cinema. It interrupted the narrative flow, yet made the whole experience seem more interactive. Unfortunately, the art of choosing where to place side breaks was lost on many LD companies. The absolute worst disc was LIVE's Reservoir Dogs, which actually cut a sentence in half! But all in all the inconvenience was nowhere near being a dealbreaker.

Soon my Alien3 disc had plenty of silvery friends to keep it company, partially fueled by the discovery of the Columbia House laserdisc club. Despite the fact that they charged $8,000 for shipping and handling, I managed to eke out a few good deals on boxed sets. My first pair of real speakers followed shortly thereafter - a set of Advent Prodigy Towers. My hand-me-down Kenwood receiver was on its last legs, so when a friend offered to sell me his used JVC stereo (complete with a partially melted faceplate from a college party gone awry), I could not resist. I still had no surround sound, but the JVC unit had hookups for both A and B pairs of speakers, so needless to say I had to hook up my parents' old Jensens for a pseudo-surround experience. The Adventures of Brisco County Jr. never sounded better.

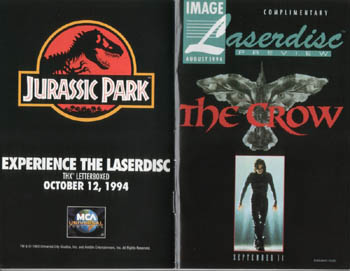

Not long after, I moved out and into the place that would house my first bona fide Home Theater. It all started in my new living room, with a miniscule 19-inch Toshiba TV plopped inside my sagging, particle board ‘entertainment center'. At this point in time I still did not own a VCR – but with a laserdisc player I didn't feel the loss all that much. That's about when Jurassic Park hit Laserdisc, and I plunked down some hard-earned coin for the absolutely feature-less CAV boxed set.

Laserdiscs were mastered in one of two ways – CLV (or Constant Linear Velocity) was the most common, wherein one side of a disc could contain one hour of program material. CAV (or Constant Angular Velocity) could only hold thirty minutes of video, but the benefit of this format was that you could freeze frame and perform slow advances and the like. Only the uber-expensive LD decks with “digital effects” could do such still-frame wizardry with CLV discs. So for a static shot of a T-Rex, you had to shell out eighty bucks.

Still, it rocked the house. Literally. As did The Crow, one of my absolute favorite fims from 1994. When it hit LD, I played it a lot . Despite the fact that my limited knowledge of speaker placement resulted in my front right speaker being buried behind the arm of a chunky sofa, this disc revealed to me the wonders of great stereo imaging. In one scene Eric Draven knocks a flying throwing knife off into the right channel, and the first time I heard it hitting the ground it sounded like it had actually happened in my living room. This Home Theater thing was getting cooler every minute.

It was in this era that I regularly visited what I considered the New England mecca for laserdiscs - Boston's Laser Craze! Granted, Tower records had a reasonably beefy supply of discs, and I never made it to Sight & Sound (also in Mass.), but the one place I adored above all others was the Laser Craze multilevel megastore on Newbury Street. They had a great selection of used discs and a wallet draining smorgasbord of Japanese imports.

Where else could you find Rush's Exit Stage Left on LD? Or the European cut of Ridley Scott's Legend with the original Jerry Goldsmith score? Or maybe even the insanely beautiful Japanese boxed sets of David Lynch's TV masterpiece Twin Peaks? If you were really cool (like Fonzie), you shelled out over a hundred clams for the import disc of Pulp Fiction while it was still playing in theaters here in the states. Laser Craze had it all, and everytime you walked in there you'd wish you had ten times the amount of money in your pocket.

Which isn't to say that the local mall-bound beasts such as Suncoast were all that bad. You could sign up for their cheesy frequent buyer's club and get a fifteen dollar coupon back every once in a while. Which would buy you half of a laserdisc. But they had a decent catalog and would special order anything in it for you, which is how I got my hands on an incredible Japanese film called Heaven & Earth (no, not the Tommy Lee Jones movie) which was impossible to find otherwise.

You wanted Metallica's Cliff 'Em All! on LD? They'd dig it up in some Californian warehouse and give you a call when it was in. When DVDs finally rolled along, they were outrageously expensive at the mall stores, but with laserdiscs it didn't matter because for the most part they were the same price everywhere. They were too much of a niche product to merit being on sale, so manufacturers' suggested retail pricing was the name of the game no matter where you shopped.

I had been reading Video Watchdog and Widescreen Review for a while at this point, and the latter was especially helpful in figuring out exactly what was up with aspect ratios and all that jazz. Widescreen Review was (and still is) a tech-heavy magazine that didn't waste time explaining things to newbies, yet was an invaluable resource when it came to film and video knowledge. Unlike with many people, video letterboxing was never bothersome to me. I always found letterboxed ‘scope' films to look much more attractive than the pan and scan monstrosities.

Yet before Widescreen Review, I could never figure out why some laserdiscs (like Blade Runner, a Panavision production) would show off just how much of the image was lopped off when compared to their VHS counterparts, while others (like the Academy Flat Ratio film Batman Returns) seemed to yield disappointing results. The mag explained that 1.85:1 films actually used a mask to create widescreen images (unlike Panavision - or scope - films, where the image is actually squeezed onto the entire frame and then unsqueezed during projection), and that for video transfers it was easier to just remove this masking, revealing the entire frame (which was close to the aspect ratio of all American televisions at that time, 1.33:1).

This explained why early TV pan and scan transfers of Pee Wee's Big Adventure revealed things that were never meant to be seen on screen (like the dolly tracks underneath rolling roadway signs, or the hole in the bottom of a bicycle compartment through which a supposedly ‘endless' stream of bicycle chain was being fed through.). But enough of this nonsense, there are plenty of worthy online resources explaining aspect ratios and the benefits of widescreen video transfers.

What really rocked about Widescreen Review was that they had extensive reviews of all of the recent letterboxed laserdisc releases. The downside was that (probably due to a lack of screener copies) by the time each issue hit the newsstands you usually already owned most of the discs. Most of the time you were just reading the reviews to compare notes and to see if you were seeing/hearing correctly. Then there was the bonus of the wonderfully bad grammar peppered throughout the reviews, most of which would end with something like: “It exhibits an wonderful picture that will be sure to please.”

Those old back issues are a blast to read now, and boy if they didn't take pains to let you know that they thought DTS surround was the only acceptable 5.1 format! It might actually have been a viable cure for cancer if I remember correctly! (Not to overly slag what was/is a great mag, but their comparative reviews of laserdisc surround tracks were the utmost in hifi-geek comedy - on a scale of 1 to 5, the best Dolby Digital releases would rate a 5, while the DTS versions of the same films would rate a 5+. Yes, they literally broke the scale! If only Criterion's This Is Spinal Tap release had been encoded in DTS surround sound, it very well may have gone to eleven! That said, I do like DTS quite a bit.)

The magazine that really changed things for me in the world of Home Theater was a little publication I discovered in October of 1994 named Home Theater and Technology. Now just a shell of its former self, this magazine was a monthly wet dream loaded with reviews of all the latest audio/video gear. And surprisingly, some of it was actually affordable. This was the magazine that led me to buy my first subwoofer, a $99 Radio Shack ‘Optimus' passive cheapie. They were so affordable I eventually bought two and wired them in stereo. Of course they couldn't rock hard, but one of them still hides next to my couch now to give a little extra oomph to the surrounds. Plus, they made great footrests and/or drink tables. The necessity for these little boxes of boom was that for the first time ever, a laserdisc bottomed out my main speakers.